We are pleased to present the results of a new study recently published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences journal. This scientific paper is the result of the meticulous work of Pascale Tremblay, director of the laboratory; Lydia Gagnon, former research assistant in our laboratory; Edith Durand, speech-language pathologist and professor at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR); as well as Joël Macoir, professor at the School of Rehabilitation Sciences at Université Laval.

Introduction

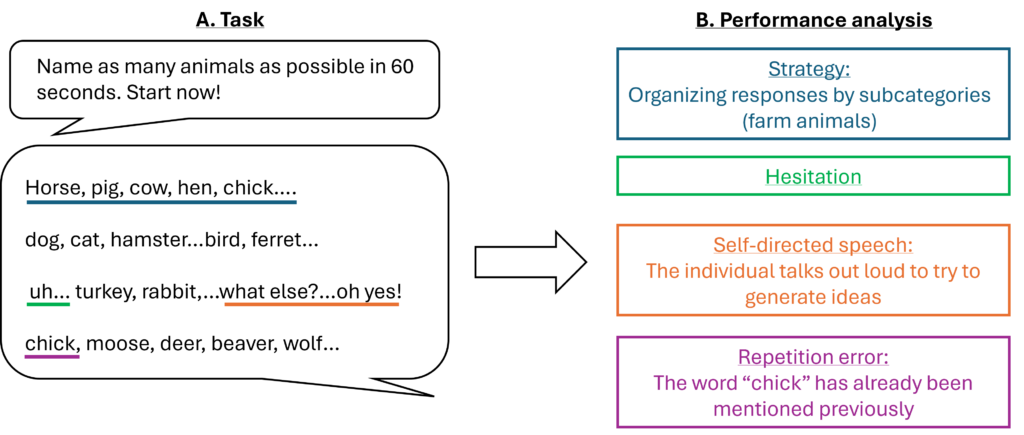

Verbal fluency is a task used in speech-language pathology and neuropsychology that involves generating words quickly according to specific rules. These rules can be, among others, phonemic (based on speech sounds) or semantic (based on a category of objects or items). Here are two examples of instructions for performing this type of task:

- Name as many words as possible that begin with the sound /p/ in 60 seconds (phonological constraint)

- Name as many animals as possible in 60 seconds (semantic constraint)

If you try this task yourself, you will notice that it can be more difficult than it seems. Indeed, verbal fluency measures several language and cognitive abilities:

a. Lexical access, that is, the ability to retrieve known words stored in our brain;

b. Working memory, which allows us to temporarily hold and manipulate several items in memory;

c. Inhibition, which helps, among other things, avoiding repeating items already produced or producing words that do not follow the instructions;

d. Cognitive flexibility, which enables us to adapt to different rules and constraints within a task.

(To learn more about cognitive functions, see this article: Cognitive functions)

Some people spontaneously use strategies to facilitate word retrieval. For example, in a semantic verbal fluency task, they organize their responses into subcategories (e.g., farm animals, savanna animals). Others use self-directed speech (talking to oneself) to try to generate ideas.

Errors made during this task can be classified into different categories. In our study, three types of errors were measured:

- Intrusion errors, when a person names a word that does not belong to the requested category;

- Repetition errors, when a person produces a word already produced;

- Non-words, that is, the production of nonexistent words.

This complex task is particularly interesting to study because it can measure changes in cognitive and language abilities that occur during normal and pathological aging [1–2]. For instance, a study recently published by Dr. Joël Macoir and Dr. Carol Hudon, professors at Université Laval, showed that people living with mild cognitive impairment produce fewer correct responses in verbal fluency compared to people with good cognitive health [3].

Our study

Our study aimed to explore the impact of aging on performance in verbal fluency tasks and potential protective factors. More specifically, this study sought to answer the following questions:

Do older adults enage in more self-directed speech during verbal fluency tasks compared to younger adults? Is that helpful? Do they hesitate more? Do they make similar types of errors? Are certain potentially protective factors linked to better fluency in older age?

Methodology

A total of 144 individuals aged 20 to 87 were recruited from the community. Four verbal fluency tasks were performed, three of which were based on phonemic criterions (words beginning with T, N, or P) and one on semantic (animal category). An analysis of correct responses, errors and hesitations, as well as self-directed speech, was conducted. The team also examined eight factors that could be associated with better performance on this task:

-

- Choral singing practice

- Level of education

- General cognitive level

- Multilingualism

- Positive attitude

- Self-reported general health

- Social participation

- Hearing

Main results

Age effect on performance

On average, performance on the semantic fluency task was lower in older individuals than among younger ones. For the phonemic fluency tasks, older women performed better than younger women. Overall, older individuals were more likely to produce repetition errors than young adults, whereas no difference was observed between younger and older participants for intrusion errors or non-words.

Use of self-directed speech

Middle-aged individuals were less likely to produce self-directed speech than younger or older individuals. On average, those who produced more self-directed speech had a lower number of correct responses during the tasks.

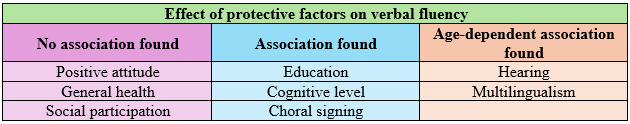

Protective factors (Figure 2)

Our analyses revealed that verbal fluency performance was generally higher among people who:

- Had a post-secondary education

- Showed a higher general cognitive level

- Participated in choral singing activities

In addition, older people with better hearing levels performed better on the task than younger adults. The results also show that age influences performance differently depending on the number of languages spoken. Among monolinguals and bilinguals, performance tends to improve slightly with age. Among multilinguals (three or more languages): the opposite occurs — performance tends to decrease slightly among older individuals.

What to take away from this study?

Self-directed speech and repetition of the same response are more frequent among older adults during verbal fluency tasks. These behaviors may reflect difficulties in ignoring previously visited ideas, but they could also represent strategies to stay focused and engaged in this demanding task.

Certain characteristics, such as post-secondary education, high cognitive abilities, choral singing practice, or hearing, are linked to better performance. However, none of these characteristics taken individually is sufficient to prevent age-related decline in performance. It is therefore more likely that a combination of several factors helps maintain language and cognitive skills over time.

You can read the full scientific article here:

Exploring Factors Affecting Verbal Fluency in Healthy Aging

Références :

[1] Kempler, D., E.L. Teng, M. Dick, et al. (1998). The effects of age, education, and ethnicity on verbal fluency. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 4: 531-538.

[2] Strauss, E.H., Sherman, E. M., & Spreen, O. (2006). A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms, and commentary. University Press. New York: Oxford.

[3] Macoir, J., & Hudon, C. (2025). Normative data for the verb fluency test in the adult French-Quebec population and validation study in mild cognitive impairment. Applied neuropsychology. Adult, 32(3), 646–652.

Suggested readings:

Priming: A Window into the Organization of Our Brain!

PICCOLO Project in Images. Part One: Impacts on Articulation

New scientific article about the impact of singing on articulation

Myth or fact: “We only use 10% of our brains”

Alexandre’s study presented at the Scientific Day of the Quebec Bio-Imaging Network (QBIN)

New Scientific Article on the Links Between Musical Activity Practice and Executive Functions

What is your brain doing when you rest?

Pascale presents our work at the “Neurosciences and Music VIII” congress in Helsinki