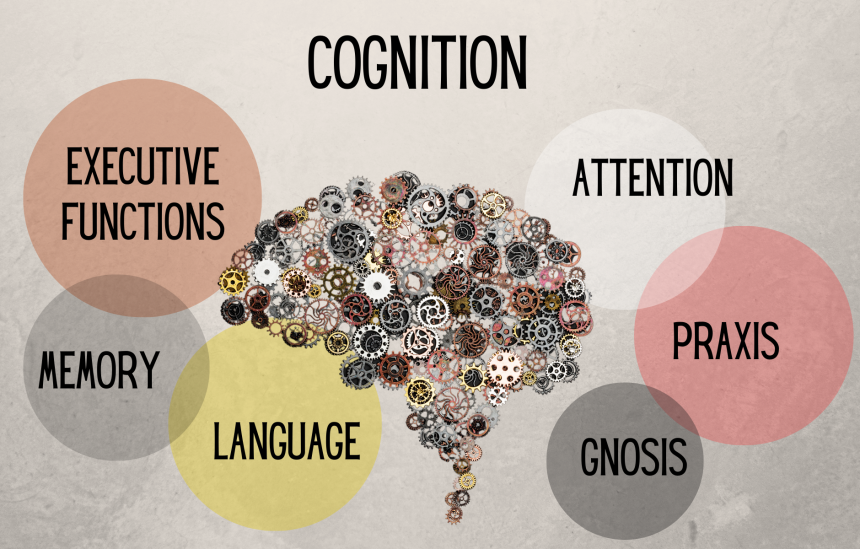

In our research projects, we often use tests that assess cognitive functions, also called “cognition”.

Cognitive functions are the mental operations involved in acquiring knowledge, manipulating information, and reasoning. They include operations related to the domains of perception, memory, learning, attention, decision-making and language (Kiely, 2014).

Our laboratory is interested in communication, which depends on these functions. For example, to talk with someone, we not only use speech, voice, and language functions, but also our memory to discuss past events, and our attention to capture the content of the message from the person we are speaking with. This is why we frequently use tests to assess cognitive functions, mainly memory and attention. For example, we can ask the participants of a research project to take an attention test to see if performance on this task affects performance on our various language tests. Indeed, a person who is less attentive to the words heard during a language task might have more difficulty to complete the language task. If we don’t measure attention separately, it will be impossible to untangle language from attention capabilities.

In this article, we give you an overview of the main cognitive functions:

Language

Language functions form a family of cognitive functions that includes a number of mental operations, allowing us to understand words and sentences, express ideas using language, etc. These operations are associated with different spheres of language, namely phonology, morphology, lexicon, semantics, syntax and pragmatics.

Memory

There are multiple kinds of memory. Memory can be short-term (e.g., remembering a new phone number for a few seconds or minutes by repeating it mentally) or long-term (e.g., remembering our parents’ phone number, which we have learned so long ago, by heart)

Memory can be verbal (e.g., memorizing words that are heard) or nonverbal (e.g., memorizing sounds in an environment).

Whether the information is verbal or not, the memorization process involves many steps. The information must first be encoded, which usually involves paying attention to what surrounds us, otherwise the information cannot be retained. The information is then temporarily held in the short-term memory before being consolidated – that is, before being stored in the long-term memory. It should be noted that not all the information stored temporarily in the short-term memory will be consolidated. However, learning implies consolidation; this is to say that when we’ve learned something new, it means that the information has been stored in the long-term memory (Lezak et al., 2012).

There are different types of short- and long-term memory (Lezak et al., 2012; Ska & Joannette, 2006), including the following:

- Phonological memory. This type of short-term memory makes it possible to temporarily maintain verbal information (e.g., retain the words that a personhas just spoken, for example their phone number, which is essential in order to analyze all the information and then give a meaning to the message).

- Episodic memory. This type of long-term memory allows us to recall our personal memories, which can be located in time and space (e.g., remembering our first day of school).

- Semantic memory. It is the long-term memory of general knowledge and facts, which are not associated with a specific place and time (e.g. knowledge of words, the alphabet, the function of objects, etc.).

- Procedural memory. It is a type of long-term memory, that of learned gestures, which are difficult to verbalize (e.g., riding a bicycle).

In our laboratory, we primarily measure phonological memory, in part because our tests of communication skills frequently involve temporarily holding syllables or words in memory (e.g., to determine if they are identical or different). Thus, to distinguish memory capacities from communication capacities, such as distinguishing the ability to memorize sequences of sounds from that to distinguish the different sounds of speech, we must use tests that allow us to measure these two skills.

Gnosis

Gnosis refers to the functions that make it possible to recognize objects through the senses (vision, hearing, touch, etc.). Gnosis depend on sensory perception and acquired memories. For example, to identify an object visually, perceptual processing must be carried out, consisting of extracting and integrating the elementary components of the image from the retina (e.g., curves of image lines, corners, etc.). The mental representation of the image thus formed can be related to the representation of the shape of the object already stored in long-term memory, allowing us to access all of our knowledge associated with the object, and to recognize it (Riddoch & Humphreys, 1987).

When we ask our lab participants to name pictures, gnosis (more specifically, visual gnosis) is involved! Indeed, before finding the word corresponding to the image, the person must first recognize the object that is illustrated.

Praxis

Praxis refers to the mental operations that allow the voluntary execution of gestures through the initiation, positioning, coordination and adaptation of isolated or sequential movements (Lezak et al., 2012). Several cognitive operations are necessary to perform a voluntary gesture, in addition to the motor operations. For example, if we are asked to use a toothbrush, we must, among other things, access our knowledge related to the function of the object (the toothbrush, how it is held, and used) and access in memory the sequence of movements to be performed before we can start the action (Rothi et al., 1991).

This category of cognitive functions is less often evaluated in our laboratory. However, one student who will be starting a master’s degree with us in September, Marjorie, will be studying the potential of brain stimulation to improve speech in people with apraxia of speech or AOS. People with AOS present a difficulty with the praxes related to speech – that is, a difficulty in planning and programming the movement sequences of speech.

Executive Functions

Executive functions relate to the set of functions that generate and control voluntary behavior directed towards a goal (Capron, 2015). They allow complex, new, or non-automatic tasks to be carried out. (Bonnaud et al., 2004). They include skills related to problem solving, such as abstraction, planning, organization, strategic thinking and self-monitoring (i.e., the ability to self-assess and regulate behavior), as well as inhibition (Troyer et al., 1994; Diamond, 2012).

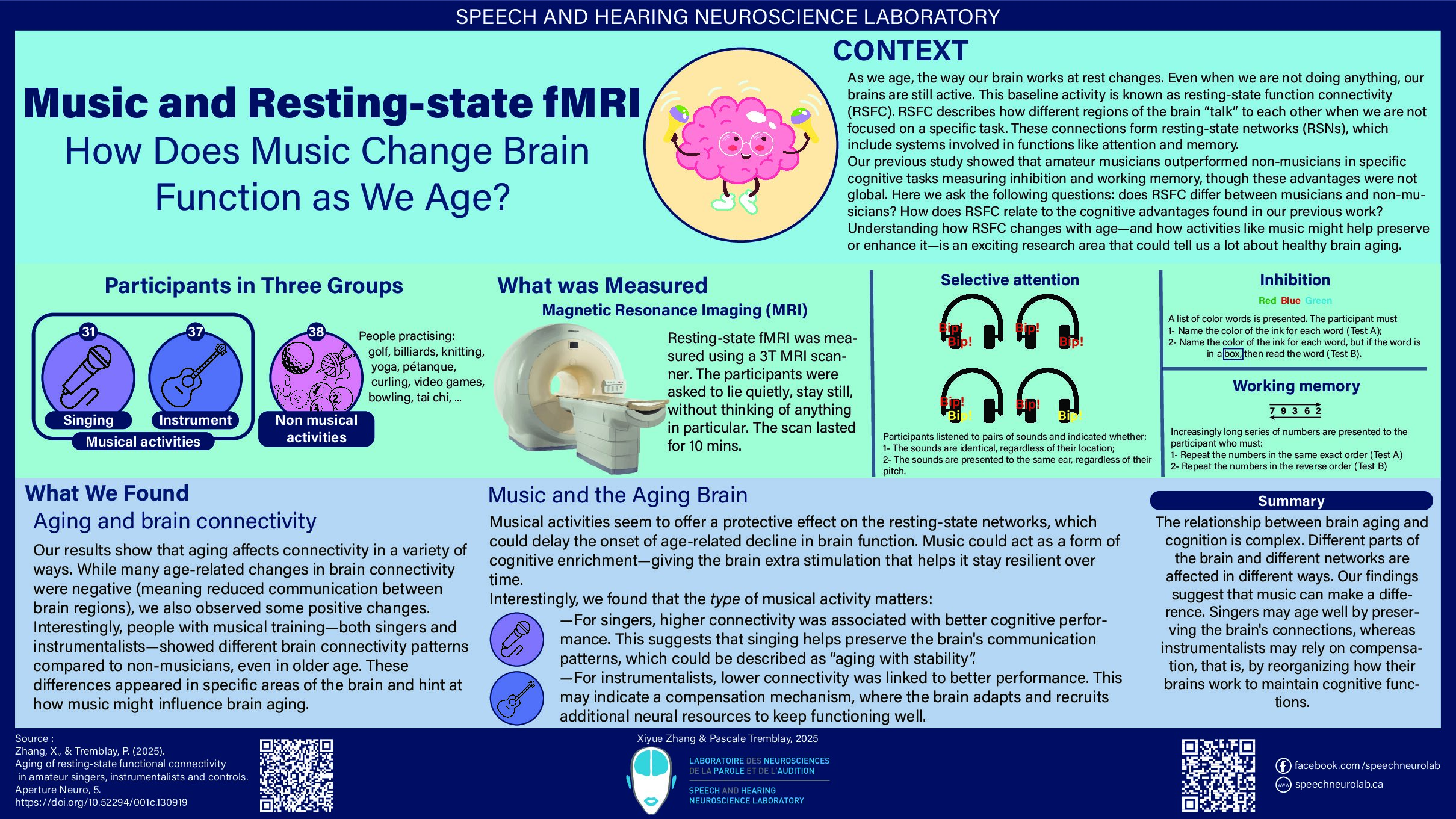

Working memory, the ability to mentally manipulate information (involved, for example, when performing mental calculations) is also considered to be an executive function (Diamond, 2012). This is a function that we are currently measuring as part of our research project on the effects of musical and non-musical activities on the adult brain on language, cognition and emotional processes! Indeed, the ability to concentrate could be improved by practicing musical activities, but this has yet to be demonstrated!

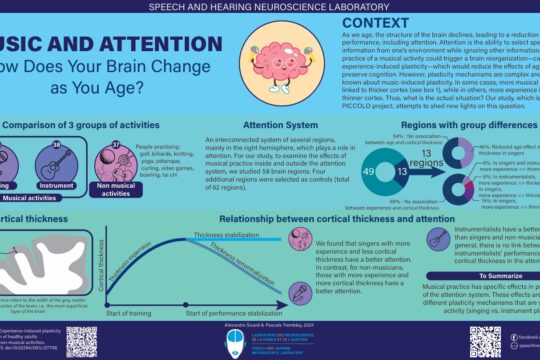

Attention

Attention is a complex cognitive function referring to the ability to be receptive to one’s surroundings. It is possible to distinguish several types of attention (Lezek et al., 2012), including:

- Selective attention. It allows us to focus on something or an idea, ignoring distractions in the environment.

- Sustained attention. This allows us to keep our attention on something for a certain period of time.

- Divided attention. This type of attention refers to the ability to perform two tasks at the same time or to pay attention to several elements of the same task simultaneously.

- Alternating attention. It is the ability to focus our attention alternately on different elements of the environment.

During the experimental tests carried out in our laboratory, several types of attention may be involved. For example, to perform a speech-in-noise perception task, selective attention comes into play to ignore surrounding noise, and sustained attention is also involved if the test takes a long time to complete. Thus, each time we prepare a new experimental task, we must think about the different cognitive functions that will be involved, and plan, if necessary, for the inclusion of additional tests that will allow us to control or measure their contribution to the main task.

Finally, it is important to mention that the expression “cognitive functions” has several definitions. For example, although attention is often presented as a cognitive function, it is also often seen as an executive function (Diamond, 2012). In addition, attention and executive functions are sometimes viewed separately from cognitive functions, as they are related to the efficiency with which mental operations are performed (Lezek et al., 2012). Finally, the cognitive functions of language are often talked about, but we must not forget that there are also several mental operations involved in speech, not just language!

This brief overview of cognitive functions reveals how complex communication is, and how it relies on a very large inventory of cognitive functions. These functions are not just for communication, but also for accomplishing a variety of daily activities, such as planning our day, remembering what we did the previous night, or staying focused at work!

To find out more about cognitive functions, you can consult this page of the Quebec Association of Neuropsychologists’ website: https://aqnp.ca/la-neuropsychologie/les-fonctions-cognitives/ (Only available in French)

Suggested readings:

References:

Bonnaud, V., Bouston, A., Osiurak, F., & Gil, R. (2004). Le syndrome dysexecutif chez la personne âgée : de la théorie à la pratique. La Revue Francophone de Gériatrie et de Gérontologie, 11(103), 147-149.

Capron, J. (2015). Examen des fonctions cognitives en médecine interne. La revue de médecine interne, 36,818-824.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Kiely, K.M. (2014) Cognitive Function. In: Michalos A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_426

Lezak, M.D., Howieson, D.B., Bigler, E.D., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Riddoch, M.J., & Humphreys, G.W. (1987). Visual object processing in optic aphasia: A case of semantic access agnosia. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 4(2), 131–185. DOI: 10.1080/02643298708252038

Rothi, L.J.G., Ochipa, C. & Heilman, K.M. (1991). A Cognitive Neuropsychological Model of Limb Praxis. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 8(6), 443-458. DOI: 10.1080/02643299108253382

Ska, B., & Joannette, Y. (2006). Vieillissement normal et cognition. Médecine/Sciences, 22(3), 284-287. DOI: 10.1051/medsci/2006223284

Troyer, A.K., Graves, R.E., & Cullum, K.M. (1994). Executive functioning as a mediator of the relationship between age and episodic memory in healthy aging. Aging and Cognition, 1, 45–53.