New scientific article about the impact of singing on articulation

We are pleased to present to you the results of a scientific article that we recently published in the Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, and which was featured in Jean Hamann’s publication in ULaval Nouvelles in December.

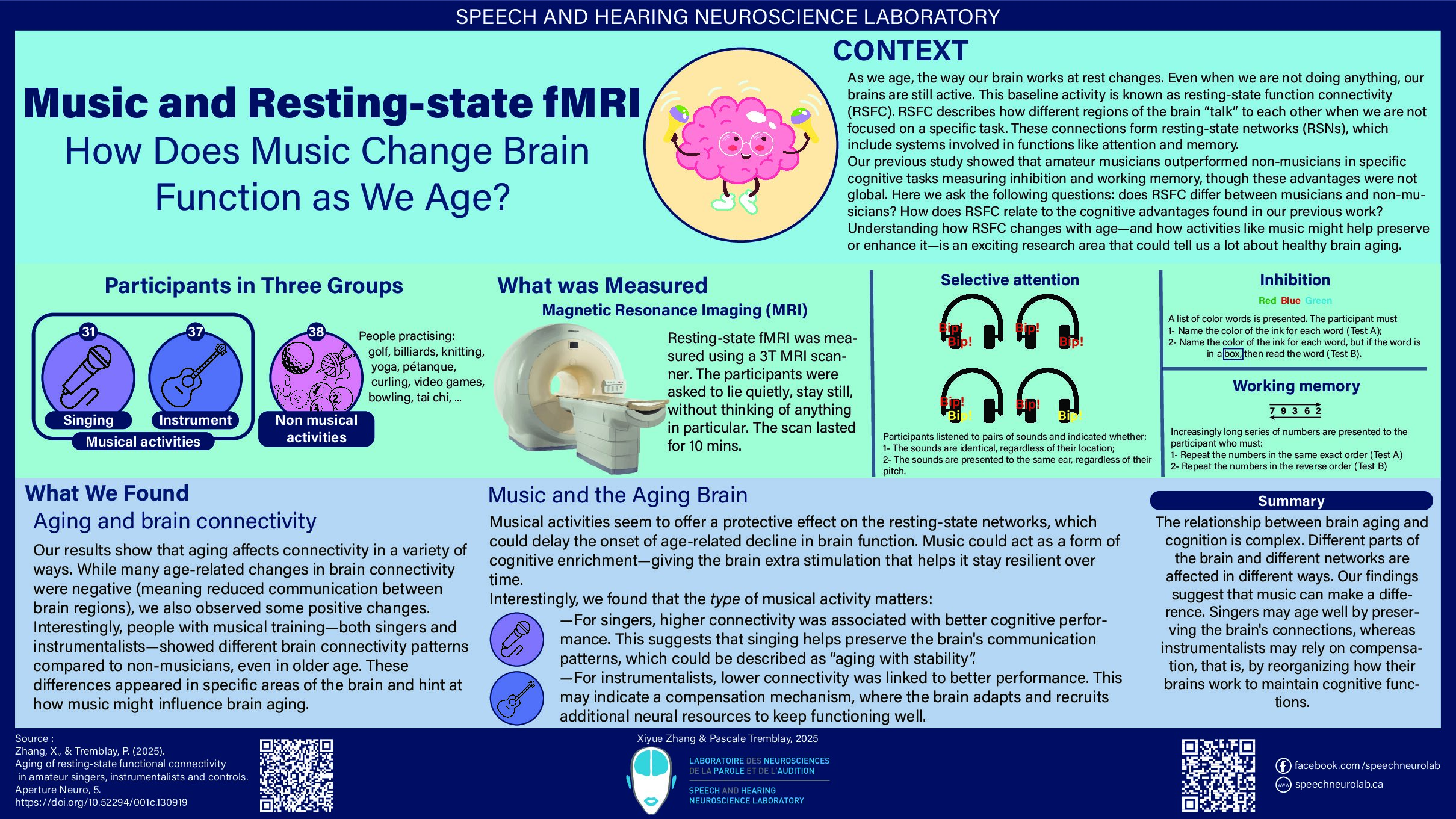

This project, funded by a team grant from FRQNT, started in 2018 after receiving approval from the Ethics Committee in Neurosciences and Mental Health Research of the CIUSSSCN of the National Capital (#2019-1733). It concluded four years later, in the spring of 2023, after overcoming various challenges, including the COVID pandemic. This extensive project focused on the effects of aging on communication in individuals who engage in both musical and non-musical activities with a motor and cognitive component (such as billiards or knitting). We have named this project ‘PICCOLO’, which stands for ‘Projet de recherche sur les effets de la Pratique d’un Instrument ou du Chant sur la COgnition, le Langage et l’Organisation cérébrale’ (or ‘Research project on the effects of musical instrument practice or singing on cognition, language, and brain organization’; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Research Project on the Effects of Practice with a Musical Instrument or Singing on Cognition, Language, and Brain Organization (PICCOLO)

While the linguistic components of language, such as semantic preparation and vocabulary, remain relatively stable over time or even become larger, the motor stages of speech production—namely, breathing, articulation, and phonation (i.e., voice production) (Figure 2)—undergo significant changes with age, displaying considerable interindividual variability. The causes of these difficulties are still not well understood, and as a result, there are few prevention strategies.

Figure 2. The stages of speech production

The hypothesis of the project was that older singers would have greater vocal quality and more precise and faster articulation than older non-singers due to their vocal training. Since singing relies on both voice and articulation, it is indeed possible that singing practice has a beneficial effect on language production (a phenomenon often referred to as ‘transfer’), although theoretical models do not agree on this point. Some models propose that speech control is carried out by a brain network distinct from the one that controls other functions of the vocal apparatus, such as laughing, singing, or shouting. Other models suggest a shared neurological apparatus. While the first type of models does not predict any effect of singing on speech, the second type predicts the opposite.

During the data collection sessions, tests measuring phonation and articulation were performed by 38 amateur singers aged 20 to 87, and 40 individuals engaged in non-musical activities with a motor and cognitive component (such as billiards or knitting), aged 23 to 88. Individuals who play musical instruments were also recruited, but their recordings were not analyzed for this article. Participants’ vocal productions were recorded.

To assess phonation, participants produced the vowel /a/ several times for 3 seconds, and then they produced the vowel /a/ for as long as possible (maximum phonation). The first task allows us to measure vocal quality and stability, while the second gives us an insight into phonatory capacity.

To assess articulation, two tests were used. The first involved reading a short text aloud. This task allows us to evaluate the precision and speed of articulation in an easy context. The second test was a diadochokinesis task, during which participants had to repeat simple and complex words and non-words, both rare and frequent, at a normal speed and as quickly as possible. This task was developed based on our SyllabO+ database, which allowed us to create highly controlled stimuli. This test evaluates the precision and speed of articulation in a context of maximal performance.

Figure 3. The project team. At the top: Lydia Gagnon (left) and Pascale Tremblay. At the bottom: Alison Arseneault (left) and Johanna-Pascale Roy

Our results show that older individuals read more slowly aloud, produce syllables more slowly and less consistently during the diadochokinesis test, and have poorer articulatory precision than younger individuals when producing complex syllables.

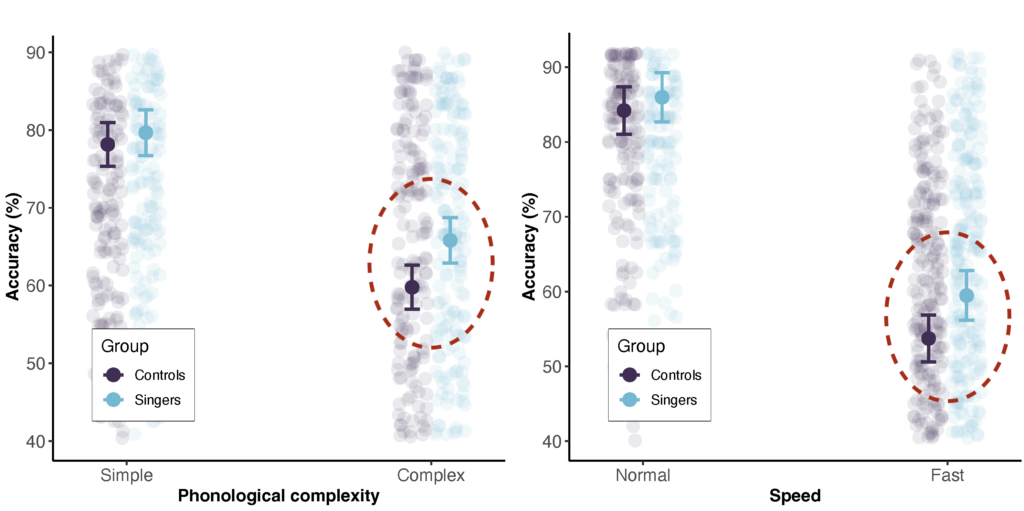

Our results also show an advantage for singers relative to non-singers in terms of articulatory precision under the most challenging conditions of the diadochokinesis task—that is, when we asked participants to produce difficult syllables (Figure 4, left image) or to speak as quickly as possible (Figure 4, right image). These findings suggest extended maximal capacities in amateur singers, possibly resulting from the articulatory efforts required during singing.

Figure 4. Results from the diadochokinesis task

Thus, this study suggests a benefit of amateur-level singing practice on speech production. However, contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find benefits on participants’ voice. This does not necessarily mean that there are none, but simply that this benefit, if it exists, was not captured in our study. It is possible that different vocal tests could reveal it.

What can be concluded from these results? Singing practice appears to have a beneficial effect on certain aspects of speech production. It is now necessary to try to identify the full range of these benefits and, more importantly, determine if individual characteristics such as age and gender, and characteristics of singing practice such as the type of singing and its frequency, modulate the benefits of singing. This information will ultimately help promote activities aimed at preventing or reducing the impacts of aging on communication.

The article can be found here: https://speechneurolab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Tremblay_etal_2023_JSLHR.pdf

The dataset can be found here: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/GHD3HE

Article by Jean Hamann in ULaval Nouvelles: https://nouvelles.ulaval.ca/2023/12/07/chanter-un-bon-exercice-pour-maintenir-la-qualite-de-lelocution-a:edaacf65-010b-40eb-99fc-063c1e603f3f