At the Speech and Hearing Neurosciences Lab, we study the neural basis of human communication using an interdisciplinary approach. This means that we draw from theories and methods across multiple disciplines to study human communication, including linguistics, but also cognitive sciences, neuroscience, psychology, gerontology, bioimaging, and computer sciences! In this post, we explore one of these disciplines, linguistics, to shed light on how linguistics contributes to our work.

Linguists are often asked how many languages they speak. The answer is usually a relatively low number, especially given that the person asking the question probably assumes that linguists are all polyglots.

Although some linguists are polyglots (more on this later), knowing multiple languages is not a requirement in linguistics. This is because linguists study the faculty of language—the cognitive system that allows us to acquire and use speech or signs for communication, and the ways in which language is structured in this system.

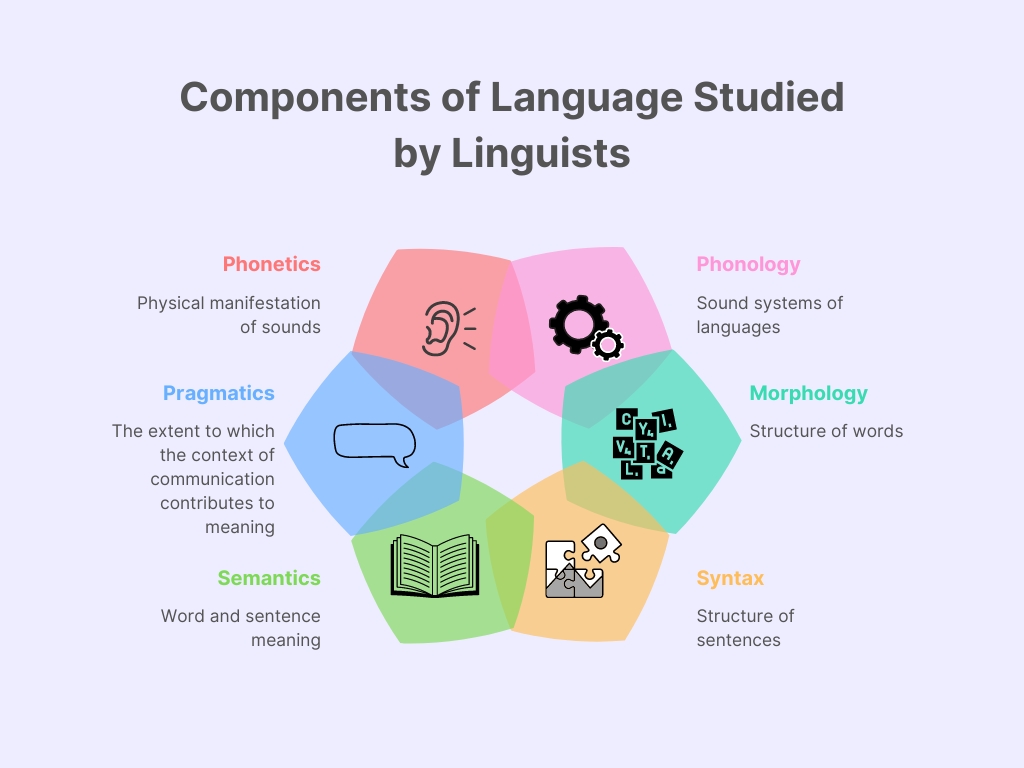

Linguists investigate the structure of individual languages to have a better understanding of how the faculty of language works. Specifically, they examine the different components of language, such as phonetics (the physical manifestation of sounds), phonology (the sound systems of languages), morphology (the structure of words), syntax (the structure of sentences), semantics (word and sentence meaning), and pragmatics (the extent to which the context of communication contributes to meaning).

Figure 1. Main fields of study in linguistics

They examine such components as a way to identify, among other things:

- which patterns are possible and which patterns are impossible across languages;

- whether some of these patterns are more difficult to learn than others (for example, for children acquiring their first language or for adults acquiring a second language);

- how patterns in a given language change over time (due to social factors or language contact, for example).

This allows linguists and other researchers not only to know more about the languages that exist (or existed at some point) in the world, but also to know more about Homo sapiens’ capacity to communicate and to learn.

So, how does one study linguistics?

Studying linguistics involves obtaining and analyzing language data. Obtaining language data can be done in many ways. For example, linguists can engage with speakers of a given language and ask for their intuitions about their language—these speakers are known as language consultants. Alternatively, linguists can use corpora to obtain spoken, signed, or written data. Another way to obtain language data is through language experiments. Here, linguists can test participants’ intuitions, check their perception of speech sounds, or have them produce certain linguistic structures. Linguists often analyze data quantitatively with statistical models.

Figure 2. Lydia and Pascale (two students with backgrounds in linguistics) conducting speech signal analyses

To study a specific language, linguists need to know how that language works. That is, they need to have a deep understanding about its phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, etc. so that they know what to ask what to search in a corpus, and how to design an experiment. However, they don’t necessarily need to know how to speak the language. Many linguists actually speak one or two languages but know a lot about dozens of them! That’s because, in linguistics, it’s important to know about the structure of a given language in order to study it—and we can have this kind of knowledge without speaking that language fluently.

Another question that linguists get a lot is “What language do you study?”. While it is true that some linguists specialize in a particular language (such as French) or language family (such as Romance, the language family to which French belongs), most linguists do not do research on a particular language. Instead, they may be interested in a specific topic related to language and study that topic across different languages. For example, a phonologist’s research may focus on vowel reduction—which is when a vowel is perceived as “weaker” depending on factors such as prominence and position in the word; for example, compare the first vowel in origin (a full vowel) with the first vowel in original (a reduced vowel). Phonologists who study vowel reduction can examine how this process works in languages such as English, Portuguese, Russian, and even “dead” languages such as Latin!

Now that we know what linguists do, it’s also important to mention where they work. People with a degree in linguistics can work in various jobs related to language. Here are some examples:

- linguists can work in research, including in universities. For instance, our former lab coordinator Natália had a PhD in linguistics. Nathan, Lydia and Pascale have an undergraduate degree in linguistics!

- linguists can work in education by teaching a (foreign) language, training teachers, developing resources for teaching, and preparing/assessing standardized exams;

- linguists can also work as translators, interpreters, proofreaders, and lexicographers (those who develop dictionaries);

- linguists can work with underdocumented or endangered languages by developing educational, documentation or revitalization projects;

- linguists can work for the government in positions that involve translation or data analysis. Federal agencies such as the FBI and the CIA (in the USA) and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service often hire linguists;

- linguists sometimes join graduate programs in speech-language pathology, neuroscience, and psychology—as well as graduate programs in linguistics;

- linguists can work in the tech industry, in positions that involve speech recognition, artificial intelligence, natural language processing, and speech synthesis.

Although linguists usually don’t speak many languages, they do share a passion for understanding how language works and what language can tell us about our cognition and social behaviour.

Suggested readings :

- Cognitive functions

- Cutting up language to study its inner workings!

- Difference between speech, language and communication

- How are language experiments created?

- Natália’s Departure

- Québécois French as an inclusion criterion

- Scientific publications

- Speech analysis

- Speech perception: a complex ability

- The profession of speech-language pathologist

- Voice production

- What is prosody?

- What is the most important element of communication?

- Who works in our lab?