New Scientific Article on Brain Mechanisms Affecting Speech Production in Aging

We are excited to share the findings of a recent scientific article from our team, exploring the mechanisms underlying speech production challenges during aging

Speaking is a fundamental aspect of human communication, often perceived as natural and effortless. However, it relies on complex motor and sensory processes. A speaker must not only plan and produce intricate sequences of sounds but also perceive and adjust their speech based on acoustic feedback. Aging affects speech production quality, making it slower, more variable, and less intense. However, the exact mechanisms behind these normal age-related changes are unknown.

This led Pascale Tremblay, our lab director, and her long-time collaborator Marc Sato (University of Aix-en-Provence) to investigate the brain mechanisms supporting speech production. Their findings were recently published in the international journal “Brain and Language.” The team examined whether two fundamental speech motor control mechanisms are impacted by aging, potentially explaining the changes in speech production with age. Using electroencephalography (EEG), a non-invasive method that records neuronal electrical activity (to learn more about EEG, click here), they measured evoked potentials, i.e., brain activity changes triggered by stimuli (e.g., sounds).

The team examined two specific mechanisms in younger and older adults: Movement-Related Cortical Potential (MRCP) and Speech-Induced Suppression (SIS).

First mechanism, MRCP, relates to motor planning of movement. Before producing a sound, a change in brain electrical activity occurs. This negative brain response appears one to two seconds before the sound is made, indicating necessary planning occurring across various brain regions. EEG can be used to record this signal both during self-paced sound production, where individuals produce sounds at their own rhythm, and during more controlled production, such as when following an imposed pace. In our study, we hypothesized that MRCP would be higher in older adults, reflecting increased effort in planning speech tasks, likely due to reduced neuronal efficiency.

The second mechanism, SIS, pertains to auditory-motor integration during speech. It enables us to process our own voice differently from others’. When speaking, our auditory cortex shows reduced response to our voice compared to external sounds, allowing for effective anomaly detection and correction. In other words, when we speak, our own voice is suppressed in the auditory cortex, allowing it to more effectively identify and correct anomalies in our speech production. This phenomenon also facilitates the seamless integration of auditory information, preventing interference between the acoustic feedback from others’ speech and our own during conversations. A compromised SIS would hinder proper vocal adjustments, as one’s own voice would no longer be correctly processed. EEG can measure auditory potentials, located in the auditory cortex, during voluntary sound production and perception. In our study, we aimed to determine if aging diminishes SIS, impacting speech production accuracy.

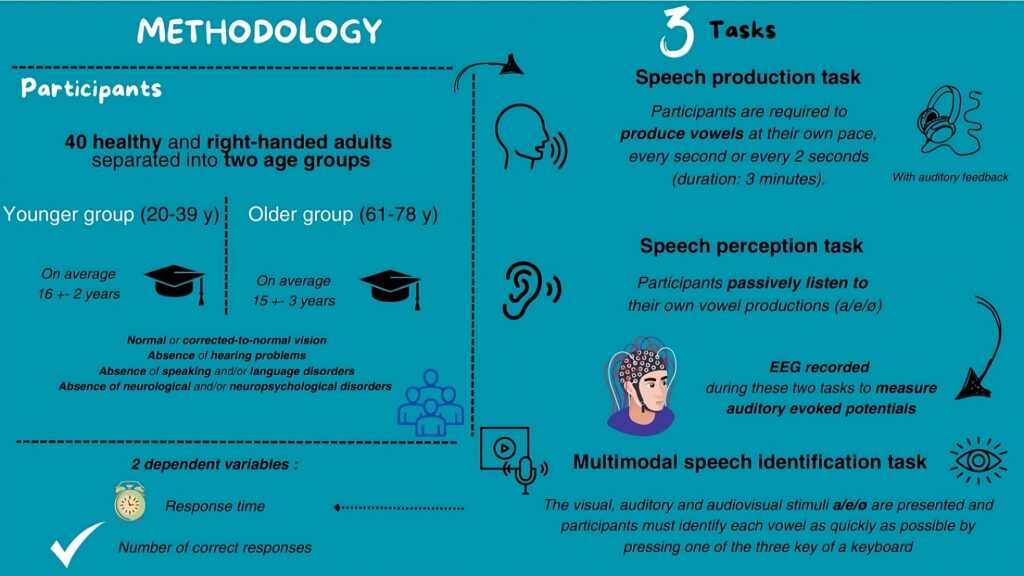

Methodology

To assess the SIS and MRCP, 40 right-handed (to learn more about lefties in cognitive neuroscience, click here), healthy French-speaking adults from two age groups performed two tasks: voluntary vowel production, then perception of them (see a summary in Figure 1). During these tasks, brain responses were continuously recorded via EEG, and results were compared between younger and older groups. A third task, named multimodal speech identification task, evaluated speech, hearing, and visual abilities. Figure 1 illustrates the modalities of the experiments conducted with the 40 participants.

Results

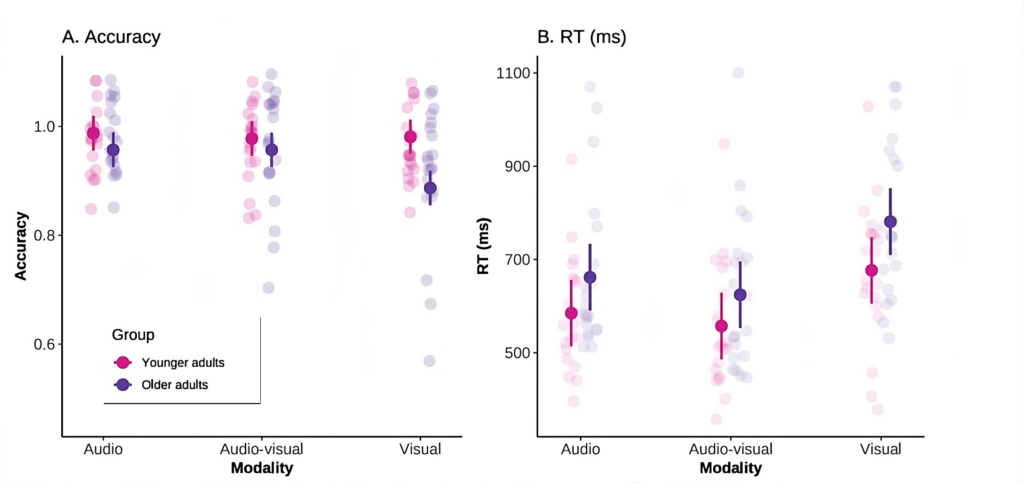

During the multimodal speech identification task, response times and accuracy were measured. Response time refers to the interval between the presentation of a stimulus (audio, visual, or audiovisual) to a participant and the moment they initiate a response by pressing a key on the keyboard. The older group demonstrated lower accuracy, especially in the visual modality, and longer response latencies across all modalities (auditory, visual, audiovisual) (see Figures 2A & 2B for these results). This confirms a decline in speech, hearing, and visual abilities with age.

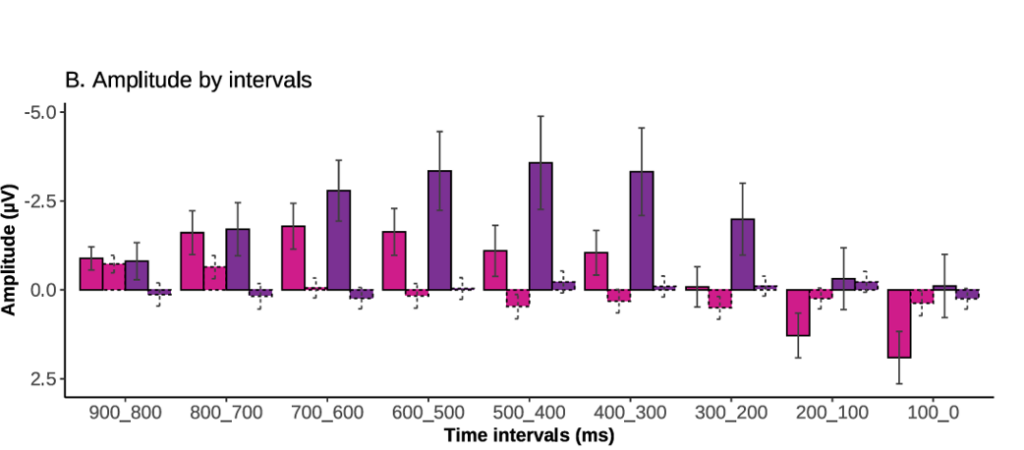

Significant differences in MRCP were observed between older and younger individuals during vowel production and perception tasks. Indeed, older participants showed higher MRCP amplitudes during the preparatory phase (see Figure 3), during the self-paced vowel production task (task 1), indicating greater neural resource demand for sound production.

Regarding the SIS, first it is important to keep in mind that the SIS is higher during passive listening than during voluntary sound production (as the brain response to our own voice is suppressed). A reduced SIS (i.e. a reduced suppression, meaning a larger SIS) would therefore indicate a compromised system, unable to suppress the auditory response to our own voice and less efficient in adjusting production. However, the results of the study do not support this. Indeed, results of tasks 1 and 2 showed a stable SIS in older participants, with higher suppression during sound perception than production, suggesting preserved auditory-motor integration.

This study highlights that speech motor difficulties in aging stem from less efficient motor preparation requiring increased cerebral activity, while auditory-motor integration remains intact. These insights are crucial for developing solutions to improve speech production and overall well-being in older adults.

Suggested readings :

- Electroencephalography (EEG)

- Combining MRI and EEG with brain stimulation: An ambitious project!

- Speech production and trumpet

- ‘Muscular’ speech production

- Comic strip about speech

- PICCOLO Project in Images. Part One: Impacts on Articulation

- Difference between speech, language and communication

- How does brain aging affect communication?

- Pascale holder of a Canada Research Chair 🇨🇦