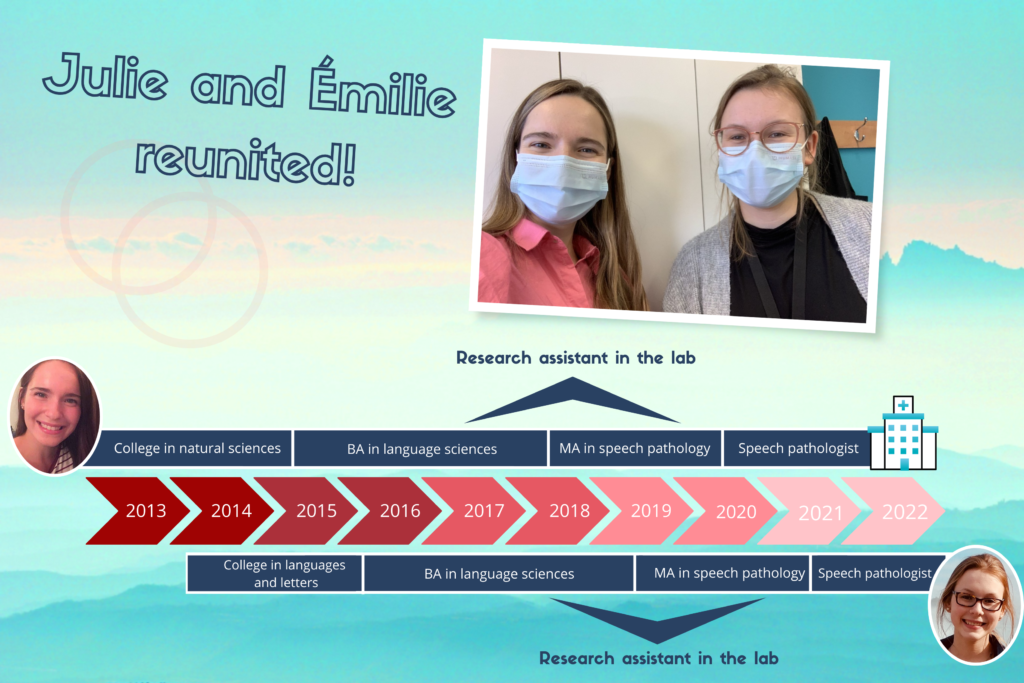

***This blog post was originally published in French in December 2021.***

The life paths of some people are sometimes intertwined by chance… This is the case of Julie and Émilie, who were both research assistants in our lab during overlapping periods, and who now find themselves as colleagues in their current professional environment!

We were curious to learn more about Julie and Émilie’s journey since they left the lab. Marilyne, research associate at the lab, contacted them for a brief interview.

Here are the questions and answers from this interview:

Q – While you were still working at the laboratory, you both started a professional master’s degree in speech-language pathology at Université Laval. You have now completed your training (Julie in 2020 and Émilie in 2021). Where do you practice your profession and who are your patients?

Émilie – We both work in a hospital setting, but with different types of patients. I have recently started this job! I work with children aged 0 to 5 years who have a medical condition or who were born prematurely. I perform assessments to determine if their language skills are developing well. For some hospitalized children, I also conduct bedside language skills evaluations at the request of doctors or nurses, to investigate if they need services and to direct them to the right place if necessary (for example, to a CLSC or a rehabilitation center).

Q – What type of medical condition can the children you meet have?

Émilie – It can be any medical condition that may lead to language difficulties. For example, children with epilepsy or neurofibromatosis (a genetic disease that affects the nervous system).

Q – I imagine that conducting evaluations at the children’s bedside must be challenging.

Émilie – Yes, it’s a unique context! We enter the patient’s and their parents’ private space. In general, we need to intervene quickly, and we use the toys in the room due to certain protective measures. So, we have to innovate and ask a lot of questions to conduct our evaluation! However, most of my interventions happen in my office, with children who have external follow-ups and who come to the hospital with their parents.

Q – And you, Julie?

Julie – For my part, I’ve been working at the hospital for just over a year. When I arrived, I worked in pediatric dysphagia, that is, with children who have swallowing disorders. Unlike Émilie, I work a lot in acute care, that is, at the patients’ bedside. I am often at the neonatal unit working with newborns who have feeding difficulties (breastfeeding or bottle-feeding) and their parents, but I also go to other units to work with older children with swallowing difficulties. I also have some occasional external follow-ups. So, it’s really varied! I collaborate with lactation consultants, nutritionists, occupational therapists, as well as nurses and doctors, so my work is always done in a multidisciplinary team.

Q – Up to what age are the patients you meet?

Julie – They can be aged 0 to 17 years. For example, I can work with a hospitalized child who has swallowing difficulties after a stroke. However, I mainly work with infants. In addition to my work in dysphagia, for three months now, I have also been working with another clientele, namely children who stutter.

Q – Had you worked with this kind of patient before?

Julie – Yes, I did my internship in speech-language pathology in pediatric dysphagia and stuttering. The combination of these two groups of patients is interesting. Swallowing and speaking are two “mechanical” actions. (These actions involve coordinated and precise movements of the muscles of the mouth, tongue, larynx, etc.!)

Ring, ring! (The phone rings.) Julie is being called for a dysphagia intervention, for a baby with a cleft lip and palate (a split in the upper lip that extends to the palate), who needs a special bottle for drinking. Julie is often called during meal times, as this is when patients eat and she can perform her work more easily. The interview continues a bit later…

Q – Let’s talk a bit about the lab. Looking back, what do you remember or what did you appreciate the most about your time in the lab?

Julie – What was nice about the lab was working with people from different backgrounds, such as linguistics, biomedical sciences, medicine… This prepared us to interact and work with people who have different visions and areas of expertise from ours, as we currently do in our job.

Émilie – That’s true! I would also say that working in the lab helped us develop a work methodology. The work was very organized, and we used multiple Excel spreadsheets… This experience allowed me to develop tools for working in an organized, clear, elaborate, and precise manner. Since we meet several patients in a day and need to intervene quickly in some situations, having a good work methodology is important to easily find our way in our files and to more easily resume a task interrupted by another more urgent one.

Julie – In the lab, we also learned a lot about the mechanics of speech, which prepared us well for our work in clinical practice.

Émilie – In addition, we used the International Phonetic Alphabet a lot! It helps to quickly transcribe the results of a phonological assessment (a test to evaluate the ability to pronounce different speech sounds). Another aspect I developed is my critical thinking, especially in learning to question myself when reading scientific articles. In my work, this is useful, for example, in determining the reliability and validity of a test, and therefore in having a more critical view of the tools I use.

Julie – We also take the decision to look for answers to our questions in scientific databases more often. This is something we learn at school, but since we had to do it as part of our work in the lab, we are more inclined to do it and also faster in searching the databases. We can thus base our recommendations on evidence-based data. For example, if I read in scientific articles that patients with medical condition X are at risk of silent aspirations (a swallowing difficulty where liquids and food pass into the lungs without any visible manifestation like coughing), I might recommend that a patient with this condition undergo a videofluoroscopy.

Q – Could you provide a brief definition of videofluoroscopy for our readers?

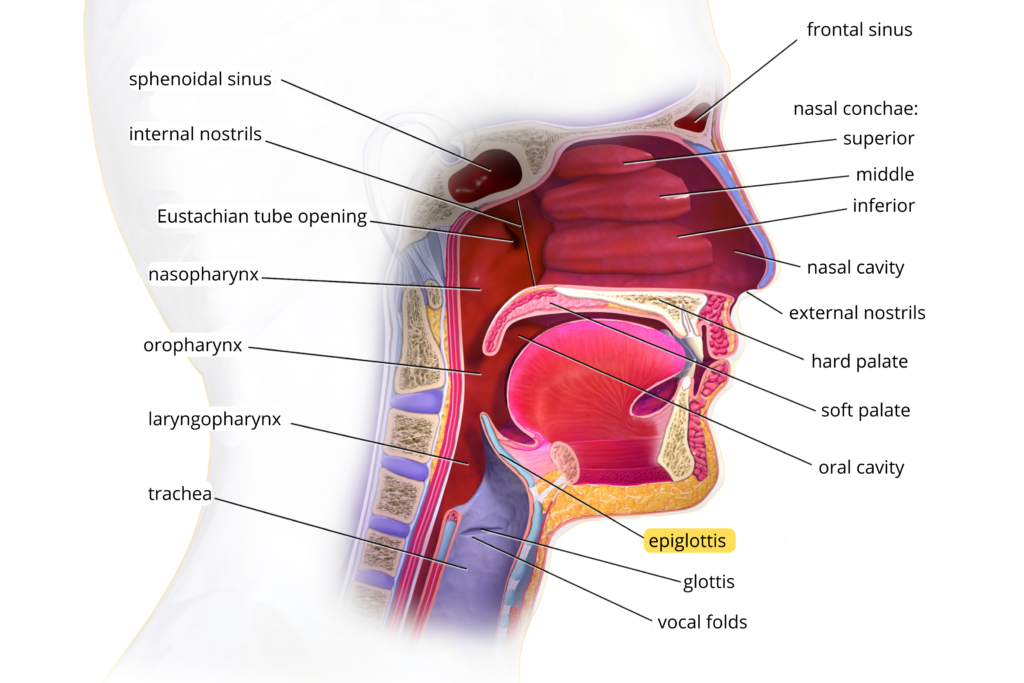

Julie – It’s an X-ray evaluation that allows us to see the functioning of the swallowing mechanism in real-time, while the patient is eating. Instead of getting a picture, as is the case with radiography, we see the structures in action. This exam allows us, for example, to see if the epiglottis (a structure at the entrance of the larynx that lowers to close and protect the lungs during swallowing, see figure 1) moves at the right time, if it closes completely, etc.

Fig 1. Upper respiratory system. Image adapted from BruceBlaus under the licence CC BY 3.0.

Q – Thank you, Julie, for this great explanation! I have one last question for both of you. In your opinion, what is the most important difference between research and clinical practice?

Julie – In research, we control as many variables as possible in experiments, whereas in clinical practice, it’s important to consider the patient as a whole.

Émilie – For instance, an intervention might be proven effective in the scientific literature for patients with a specific profile, but it might not be applicable to all the patients we meet, who have diverse profiles. A recommendation supported by the scientific literature might also not suit the parents’ priorities or be feasible in their family situation. We need to consider several factors, including preferences, level of cooperation, and the patient’s medical state and condition.

Julie – The participants who came to the lab to participate in research projects were volunteers and motivated to participate, while people in acute care find themselves in the hospital against their will and might have different priorities regarding their recovery. They might also be in pain and not available to work on their skills at that moment, although they may be ready to do so later in their healing process, such as in a rehabilitation center, for example.

Q – Julie and Émilie, thank you very much for your answers and the precious time you have given us. Is there anything you would like to add to conclude?

Julie – Working in the lab was really a great experience for us, and we still think about it often!

Émilie – We still keep in touch with our former colleagues from the lab, and we’ve made some great friendships there!

Julie and Émilie, the whole lab team wishes you the best of luck in your professional careers. Feel free to come and visit us from time to time, your presence is always greatly appreciated!